Meet the Orange-Alert Shorebirds of Hilton Head Island Part 1: Black-bellied Plover

This new series will introduce readers to a small group of shorebirds whose stories say a lot about the health of Hilton Head’s beaches and wetlands. Each post will focus on one “Orange Alert” or “Yellow Alert” species from the 2025 State of the Birds report that you can see here in winter : Black-bellied Plover, Ruddy Turnstone, Sanderling, Piping Plover, and American Oystercatcher. These birds connect Port Royal Sound, the marshes and our mud flats to the larger conservation picture across the Atlantic Flyway and the Eastern hemisphere.

The 2025 State of the Birds report highlights shorebirds as some of the most imperiled birds in the United States with many species experiencing steep long-term declines. Several of the species featured in this series are now classified as “Tipping Point” birds, meaning they have lost more than half of their populations in the last 50 years and need focused conservation action. By paying closer attention to them on Hilton Head’s beaches, readers can see how local habitat, tides, and human behavior all play a part in whether these birds continue to fade or begin to recover.

What “Orange Alert” means

In the State of the Birds framework, Tipping Point species are placed into three alert levels—Red, Orange, and Yellow—based on how urgent their situation is. Orange Alert species are “birds showing long-term population losses and accelerated recent declines within the past decade.” Black-bellied Plover, Ruddy Turnstone, Sanderling, Piping Plover, Whimbrel, and Red Knot are all listed as Orange Alert Tipping Point species in the 2025 report.

What “Yellow Alert” means

Yellow Alert species are also Tipping Point birds, but their trends show a slightly more stable recent pattern. Yellow Alert species are “birds with long-term population losses, but relatively stable recent trends—continued conservation efforts needed to sustain recovery.” The American Oystercatcher is one of these Yellow Alert birds, with coordinated coastal conservation efforts helping to turn around what had been a serious decline along the Atlantic and Gulf coasts.

The Black-bellied Plover

The Black-bellied Plover is the first bird in this series for a simple reason: it has become one of my favorite shorebirds to watch and photograph. From a distance, it reads as another gray bird on gray sand, until the late-summer light hits that flash of black on the belly and the bird suddenly steps out of the background. That first sighting, years ago in August, turned a routine walk into the beginning of a long, quiet fixation.

Black-bellied Plover (non-breeding)

Since then, I’ve gone back to the same mudflats and channels to see what the plovers are doing, from fall arrival to spring departure. They are good subjects precisely because they are busy: feeding, checking the sky, shifting their weight, then freezing just long enough for a frame or two. And then there is what I think of as the classic shorebird stare—when one turns toward me, eye-level as I lie flat in the sand, and looks straight down the barrel of the lens with those dark, perfectly round eyes that feel less like a field mark and more like a question.

Black-bellied Plovers live on a much larger map than the stretch of beaches in the lowcountry of South Carolina. They breed on an open tundra in coastal Alaska and northern Canada, especially along the Arctic Ocean and on nearby islands. Their breeding range also continues west and east into the far northern coasts of Russia and other parts of Eurasia, circling the high Arctic. When the short northern summer ends, they leave away from those nesting grounds and move south in stages, dropping into coastal stopover sites along the Atlantic and Gulf to rest and feed.

By late summer and fall, some of those same birds are on our mud flats and beaches. Others keep going, pushing on to Central and South America, or even the coasts of South America. The ones you see here in winter are part of a long, looping circuit that will eventually pull them back north again, past this same shoreline, toward the Arctic light that started the whole cycle.

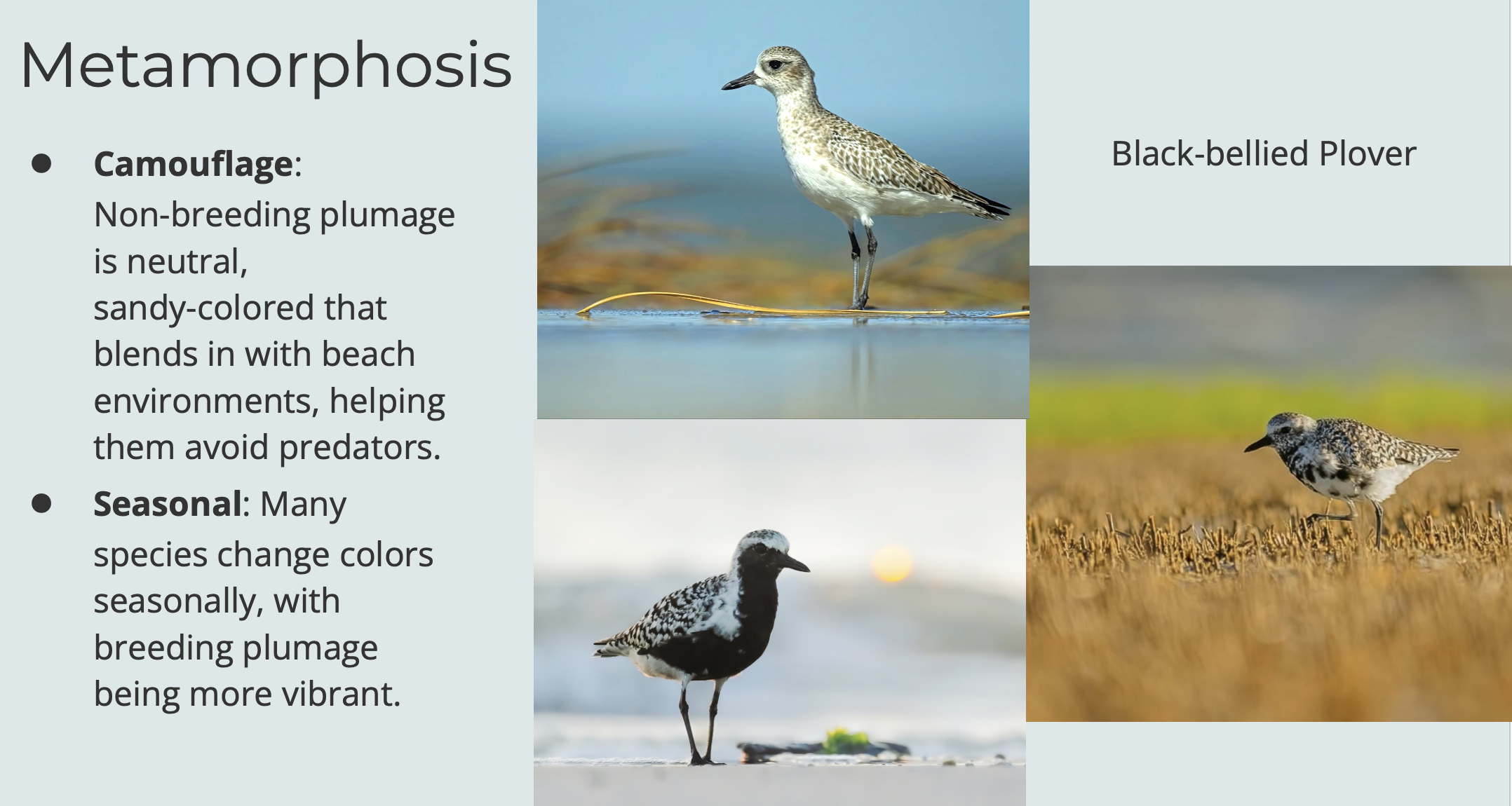

Hilton Head is a particularly good place to watch Black-bellied Plovers because the timing of migration lets you see them in more than one “version” of themselves. When the first birds arrive in late summer and early fall, many are still carrying their signature breeding look—deep black belly and chest, sharply contrasted with white, and a more strongly patterned back. As the season moves into fall and winter, that bold patterning softens into a mottled gray-and-white nonbreeding plumage, only to darken again in late winter and early spring as the black belly returns ahead of their departure to Arctic nesting grounds.

Black-bellied Plovers have a fairly stout, straight bill that is proportionally thicker and heavier than the bills of many smaller “peep” sandpipers. Their bill is medium-length—long enough to probe into soft mud or sand, but not as long or as thin as a dowitcher’s or a curlew’s bill. This shape works well for a hunt-and-peck strategy on open flats: they visually locate prey, then make quick, forceful jabs to grab it rather than deep, blind probing. It also allows them to handle bulkier items like small crabs or larger worms by seizing, shaking, and swallowing, making them well suited to the mixed invertebrate buffet that inhabit the mudflats.

On the intertidal mudflats, Black-bellied Plovers are mostly hunting small invertebrates that live just under or on the surface of the sediment. Their diet there includes marine worms (especially polychaetes and other “ragworm”-type worms), small bivalves, snails, tiny crustaceans, and occasionally small crabs and fish, which they spot visually and then grab with quick jabs of the bill. The reddish worms you may have seen them tugging out of the mud are very likely polychaete marine worms, which can be abundant in soft intertidal flats and are a major winter food source for shorebirds like Black-bellied Plovers.

My preferred time to photograph Black-bellied Plovers is just before and after sunrise, if the tide is right. I’ll often arrive in the dark and walk out toward the flats or sandbars where I’ve learned they like to feed. They really do seem like early risers. In the half-light, I usually hear them before I see them—a clear, whistled flight call (listen here)that tells me they are out there, already moving and feeding. I follow the sound, and as the light comes up, the calls turn into silhouettes, then into individual birds, each one stopping and starting along the tide line, close enough for those first low-angle portraits of the day.

Black-bellied Plover at first light of day.

How we can help

Give feeding and resting birds space

These birds need long, uninterrupted stretches of time to feed and rest so they can maintain weight for migration and winter survival.

Walk around flocks rather than through them, and give them as wide a berth as the tide and beach width allow. Disturbance forces birds to fly and spend energy they need for migration and staying warm.

Avoid flushing birds from key feeding areas on mudflats and at the waterline, especially at higher tides when roosting space is limited.

Manage dogs and beach activity

Off-leash dogs are one of the main sources of disturbance for shorebirds on many beaches.

Keep dogs leashed and away from feeding or roosting flocks, even if they “never catch anything.” To the birds, being chased repeatedly is the same as being hunted.

Steer games like running, kite flying, and drones away from areas where large groups of shorebirds are resting.

If local ordinances or programs highlight shorebird protection zones, observe the signs.

Support conservation and monitoring

Support local and regional groups like Hilton Head Audubon that protect coastal habitat, participate in community science counts when possible, and share accurate information about why undisturbed flats and beaches matter.

When you post your photos on social media, you can add a short note about giving shorebirds space and why they need room to feed and rest, helping your audience learn simple, concrete actions they can take.